Academics

August 10, 2023 2024-01-03 22:06Academics

Academics

“The single most important thing that makes a society good, and just, and wise, and happy is education” - Dr. Peter Kreeft

Our Educational Plan

Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things.

-Saint Paul

Truth

We value truth as the foundation of knowledge, fostering critical thinking skills, and nurturing students’ integrity, curiosity, and love of learning.

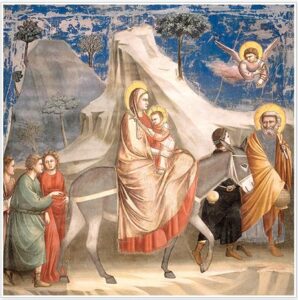

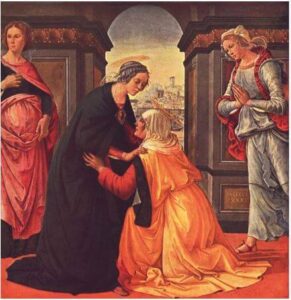

Beauty

We value beauty as an essential human experience, cultivating students’ appreciation for aesthetics, the arts, and creativity.

Goodness

Goodness is a vital aspect of students’ education, fostering integrity and a commitment to service and justice

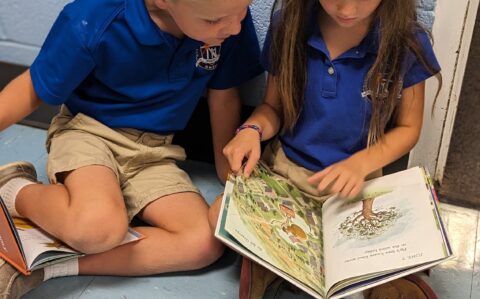

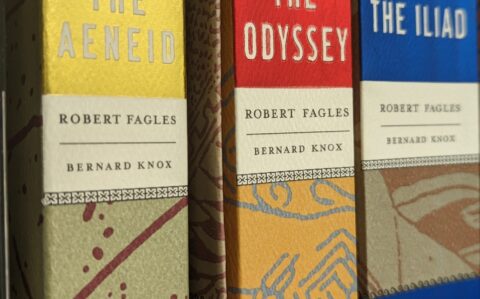

At DMA we incorporate good stories and good books into our curriculum. These are just a few of the many compelling texts our students read.